Report Data

Some studies estimate that individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DDs) comprise two to three percent of the U.S. population, yet represent four to ten percent of the adult incarcerated population. This number is likely conservative since I/DDs are often unrecognized by criminal justice professionals who are either untrained or use untailored assessment tools to identify individuals with I/DDs.

Texas has an estimated population of 29 million, which includes more than 500,000 people diagnosed with I/DDs. However, not all of these individuals receive a diagnosis or state services; thus, the number is likely much higher. Since the criminal legal system does not appropriately track data when a diagnosis is known, it is only estimated that approximately 14,700 people with I/DDs are currently incarcerated in Texas. There are presumed to be even more individuals in the juvenile justice system whose disabilities have not yet been identified.

Compounding problems for individuals with I/DDs, Texas has the highest percentage of people without health insurance in the country. Texas Medical Association data shows that 18 percent of Texans do not have health insurance, of which 61 percent are Hispanic and 10 percent are Black. The lack of health insurance coupled with the lack of unbiased medical and mental health care leaves Black and Latinx individuals without proper diagnoses and unable to access treatment options.

Furthermore, people with disabilities are commonly misperceived as:

- Unable and incapable of understanding and communicating effectively with others

- Being all the same

- Problematic to themselves, others, and society

- Unable to restrain themselves from self-harm or harming others, and unreasonable or irrational

Such misperceptions can wrongly drive individuals with I/DDs into the legal system. The Arc of Texas estimates that 50 to 80 percent of police encounters involve people with some type of disability. Black youth and young adults with a disability have a 55 percent chance of arrest compared to 37 percent for those without a disability. While the United States does not track the number of people with disabilities killed by police, the Ruderman Family Foundation estimates that one-third to one-half of all people killed by police have a disability.

Bullying, trauma, isolation, misunderstanding and misinterpretation by others, and exclusion from evidence-based therapies and preventive treatments can result in individuals with I/DDs entering the criminal legal system at higher rates than those without I/DDs. Once involved with the criminal legal system, the I/DD population faces numerous unique challenges and obstacles, such as increased victimization in jail and prison, longer sentences, and decreased likelihood of probation or parole.

Unique Vulnerabilities

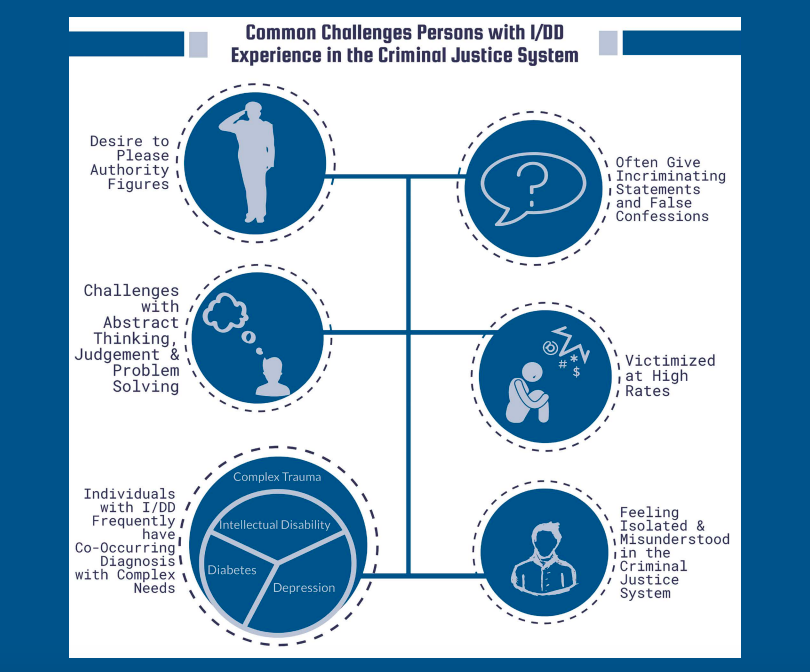

Individuals with I/DDs experience vulnerabilities in navigating the criminal legal system, which lead to more individuals with I/DDs being inappropriately assessed as a danger to the community. These individuals also remain in the criminal legal system longer than people without disabilities.

Lack of Support to Navigate the Criminal Legal System: The I/DD population often lacks the support needed to navigate the criminal legal system safely and successfully, putting them at higher risk of harm. Research suggests that individuals with I/DDs, who are not known by law enforcement to be connected to a support system or services, have a higher chance of being processed through the criminal legal system, rather than referred back to their support network and/or services within the community. Further, the potential risk or vulnerabilities of a person with I/DDs may not always be detected by criminal legal system staff.

Challenges with Communication: Individuals with I/DDs may experience communication challenges and are likely to have difficulties understanding required advisements about their basic rights. They also have higher rates of “susceptibility to suggestion” and eagerness to “please authority figures,” which can lead to unintentional “self-incrimination and confession” and increase vulnerability to coercion, deceit, and intimidation. Additionally, expressive language (how a person communicates with others) and receptive language (how a person receives communication from others) often cause confusion and miscommunication when individuals with I/DDs are communicating with someone who is unfamiliar with their communication style (e.g., grunts, gestures, or another language such as American Sign Language).

Higher Rates of Victimization: People with disabilities are three times more likely to be violently victimized than people without disabilities. In a survey of over 7,000 people across the United States, 70 percent of individuals with disabilities reported experiencing abuse, and nearly 75 percent of people with a mental health need and a disability reported experiencing abuse. Of these individuals, more than 90 percent said the abuse occurred more than once. Only 37 percent reported their abuse to authorities, primarily because they felt nothing would happen, were fearful of losing their services and supports, or had been threatened by the abuser. In more than 50 percent of the cases, when an individual with a disability did report the abuse, no further action was taken.

Those who experience childhood trauma are at high risk of entering the criminal legal system later in adulthood. People with I/DDs who experience violence, including sexual violence, may be more prone to stress in adulthood and exhibit higher rates of conflicts with peers. Further, unaddressed exposure to physical and sexual violence likely leads to increased stress and higher rates of offending in adulthood. In Travis County (Austin), Texas, it is believed that a disproportionately high number of individuals with I/DDs are arrested on felony assault charges.

Invisible Vulnerabilities: Due to prior trauma, abuse, and bullying, individuals with I/DDs may feel stigmatized by their disability and choose not to disclose it, causing their disability to go unrecognized by others, including those in the criminal legal system. When entering the system, professionals may be unaware of a disability, thus overlooking a person’s needs for accommodation and misinterpreting a person’s presentation or actions. Also due to stigma, families often reject an I/DD diagnosis label in the education system, so children might never receive supportive services and do not receive transitional services or services in adulthood. Not only does this distort data about the number of people with I/DDs, it is more challenging for individuals to connect to support later in life, which may help prevent crisis and justice system involvement.

Individuals with I/DDs often have challenges with memory, such as recalling basic information (e.g., names of group home staff, phone numbers, or their home address). They may struggle to recall event details and the sequence of events, leading to misleading statements and increasing their chances of arrest and wrongful conviction.

When under stress, such as when interrogated by police, an individual’s symptoms may be exacerbated. However, an individual with I/DDs is less likely to be restored to competency in a jail or institutional setting, decreasing their ability to advocate for themselves while incarcerated and increasing their chances of staying incarcerated.

Individuals with I/DDs are often put in segregated settings like solitary confinement, increasing the chances they will regress or mentally decompensate, which results in more disciplinary offenses and prolongs their incarceration and solitary confinement.

Lack of Access to Supportive and Preventative Services

Mental Health/Dual Diagnosis: Early intervention is essential to preventing unnecessary arrests and justice system involvement for individuals with I/DDs. Many have co-occurring needs and dual diagnoses that often go untreated or undertreated, contributing to crisis events. Approximately one in three individuals with an ID also has a mental illness like depression, bipolar disorder, and/or anxiety disorder. This population has a high rate of post-traumatic stress disorder due to their increased likelihood of experiencing sexual, physical, and mental abuse.

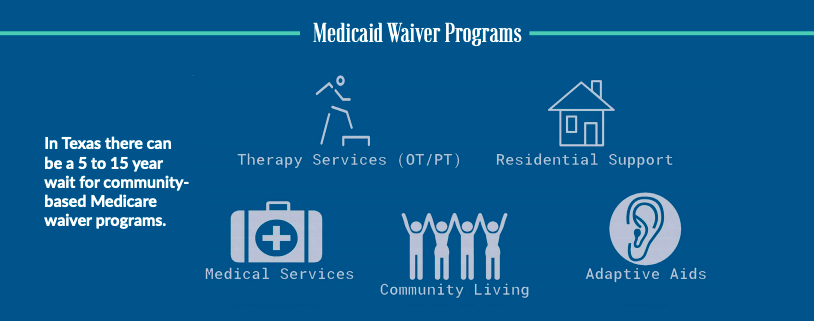

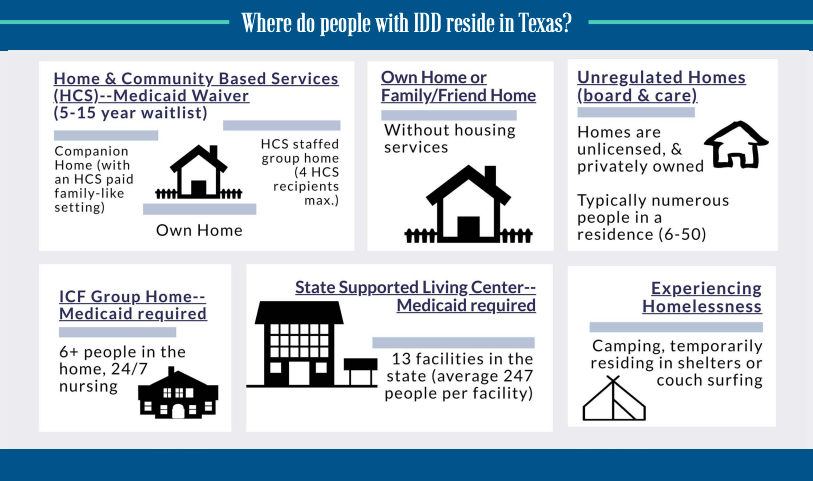

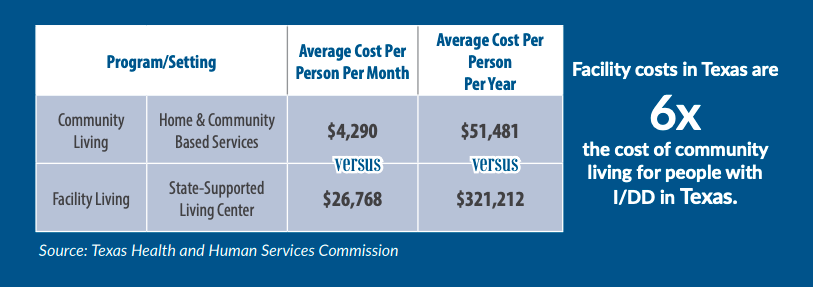

Unavailable and Underfunded Community Programs: Wait times for the Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Medicaid waiver in Texas can run from five to 15 years. Criteria for Medicaid waiver programs are narrow and require extensive historical information regarding an individual’s developmental period, which is not always accessible later in life. An individual has to be assessed by a clinician – typically a psychologist through a Local Intellectual and Developmental Disability Authority (LIDDA) – to qualify for community-based I/DD services. Many LIDDAs cannot or will not meet with individuals when they are incarcerated; thus, individuals go without services until they are released. If an individual is incarcerated for more than 30 days, their state Medicaid services are suspended or terminated and they must reapply for benefits upon release. For individuals enrolled in community-based services, the justice system often does not know how to contact the service providers to divert an individual from jail or plan for a safe release, increasing the chance of recidivism. These barriers preclude many individuals from accessing HCBS.

Lack of Access to Therapeutic Services: While community-based Medicaid services for people with disabilities cover talk therapies or other clinical recovery or evidence-based programs to address trauma or mental health needs, practitioners often incorrectly believe that people with I/DDs cannot benefit from talk therapy. Also, very few providers in Texas offer individual therapy to those with I/DDs. Unaddressed abuse and trauma can lead to stress response reactions (fight, flight, or freeze), opening another door into the criminal legal system. Easily accessible and ongoing therapeutic prevention for individuals with I/DDs will likely decrease their stress responses, which may decrease their involvement in the justice system.

An Unjust Justice System: In Texas, people charged with certain violent felonies who are determined incompetent to stand trial must wait for months in county jail to be transferred to a state hospital for competency restoration. Even with extenuating circumstances related to I/DDs that call into question the seriousness of the offense, Texas statute designates only one facility, Vernon State Hospital, to provide competency restoration for those charged with felonies involving violence. The hospital has only one unit to treat individuals with I/DDs. The entire process, from jail time to hospital admittance, often takes a year to 18 months.